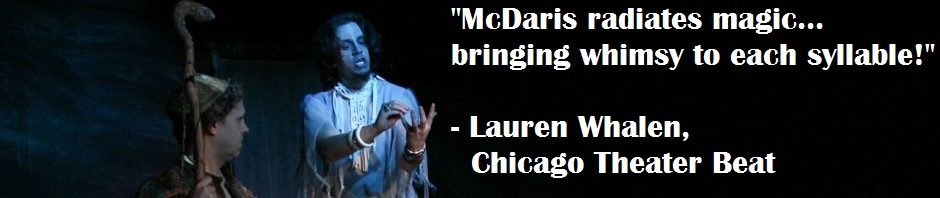

The Magistress (Lauren Miller) assertively escorts Cordelius (Jack Sharkey) to the Festival, as ‘Dame Joanne’ (Adrian Garcia) looks on, amused, in Act 3 Scene 2 of The Wayward Women

Cordelius, so used to doing what he wants when he wants, experiences a sharp reversal of fortune on the matriarchal isle of Amosa, where his reputation as a young man of “looser virtue” places him under the supervision of Dame Anu, who promises to “guard what chastity remaineth” to him. His objections to his lack of agency are somewhat ironic, since we learn from Julian that Cordelius has never been one to exercise much control over his own life.

Still, Cordelius’ lack of authority over his own life is evident in the structure of his lines. The play itself opens with his monologue, practically a soliloquy, where he bewails his misfortune. He ignores Julian’s advice and even engineers the plan that is the impetus of one of the play’s main plots. Once they enter Amosa proper, however, Cordelius no longer has any say in anything that happens. People talk about him frequently, but no one heeds his opinions on anything. He has no soliloquies, while Julian often begins or ends his scenes with them. Cordelius is rarely even allowed to enter or exit alone, and it’s only after proving his independence with sex (as many of Shakespeare’s women do, such as Juliet, Bianca, Jessica, and of course Queen Margaret), that Cordelius is allowed to enter without a woman chaperoning him.

In Act 2 Scene 2, Cordelius tries three times to assert his dominance via displaying tropes of male superiority. His first, a discourse with the Magistress, ends in patronizing dismissal. His second, a “friendly” sword fight with Dame Anu, ends in humiliation. His third, an interlude with Aquiline, ends in his own objectification, of which he does not even seem to be aware.

With echoes of the Wife of Bath, Cordelius’ journey is not so much a quest to regain his power, but rather a journey to decide which woman should possess him. As with love-torn damsels throughout literary history, the thought of not choosing a woman never seems to enter his head. Cordelius only achieves completion (and is finally allowed another quasi-soliloquy) after choosing the woman who has fought most earnestly for his affections.

Cordelius’ complete lack of agency is perhaps best demonstrated at the end of Act 3 Scene 2, where the Magistress literally, physically removes him from the scene and takes him where she wants. He objects twice to her casual abduction, and each objection is met with equally casual dismissal. Yet Cordelius, thoroughly chastened and already accustomed to following the lead, offers no physical resistance, and goes where he is led. It is particularly interesting that this sequence comes at the end of the first man-to-man moment we have seen since the play’s opening. A brief moment of two boys squabbling over a girl is interrupted when a woman reasserts her own narrative. Cordelius’ utter disbelief leaves him powerless, while Julian’s desire to maintain the power his gender-deception permits him leaves him likewise unable to affect the course of the plot.

In fact, it only now occurs to me that if there were some sort of reverse-Bechdel test, this play would almost fail it. Cordelius and Julian speak to each other almost exclusively about either Charlotte or Aquiline. The only men who are not easily distracted by women are Flachel and the Swiss Messenger, each of whom appear in only one scene.

Cordelius is a surprisingly fascinating character.

COSTUMES by Delena Bradley

LIGHTING by Benjamin Dionysus

PHOTO by iNDie Grant Productions