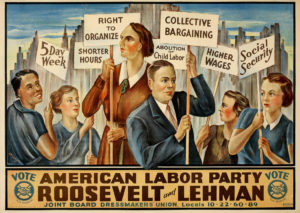

1936 Labor Party Poster; Merrill C. Berman collection

I just read an interesting article on Politico about a way off-broadway, political work, “The Trial of an American President.” In it, playwright Dick Tarlow puts George W. Bush on trial for war crimes and invites the audience to vote on his guilt or innocence at the play’s conclusion. Article author Michael Hirsh praises the work, at least conceptually, as a rare effort by contemporary theater to engage with (semi) contemporary politics. Hirsh asserts that the theater world, particularly popular theater and most especially Broadway, has long abandoned the potential controversy of Odets and Miller and now exercises almost exclusively with super-heroes, fantastic musicals, and long-defunct family dynamics.

I am largely inclined to agree with Hirsh, but working almost exclusively in the Chicago storefront scene gives me a slightly different perspective. Long-ignored socio-political issues (with a heavy emphasis on the socio) are now erupting at all levels of Chicago theater: though as always, it’s the storefronts with little to lose that promote the most strident and potentially unprofitable messages. Donald Drumpf, whose bloviation would seem beyond parody, is nevertheless being lampooned all over the place. To me, however, these productions seem at best to be congratulatory back-pats; and as often as not, they are unearned.

PARODYING THE SELF-PARODIED

In his article, Hirsh cites some laudable heavy-hitters in the yester-realm of political theater: Waiting for Lefty, All My Sons, and Angels in America are understandably prominent constellations. The classics, as Hirsh defines them (and I am inclined to agree) differ greatly from modern attempts at political commentary in that they tackle issues rather than focusing on people. The oft quoted (and oft misquoted, and possibly misquoted right here) Eleanor Roosevelt line immediately comes to mind: “Great minds discuss ideas; average minds discuss events; small minds discuss people.”

The most famous political play in a generation is a biopic celebrating a federalist icon. In Chicago, meanwhile, Drumpf parodies are popping up like weeds. Never mind for now the self-congratulatory whiff of preaching to the choir: what exactly is a theatrical indictment of Drumpf meant to accomplish? What can we get from this that we’re not already getting from SNL or from clever Facebook status updates, both of which are far less demanding of our time?

Last decade, a school that I attended staged a production of Threepenny Opera, dressing up Peachum as George W. Bush. One of my instructors rather sharply pointed out that turning a Brecht character into a contemporary luminary was antithetical to Brecht’s theories: almost everyone living already had a strong and emotional opinion about Bush. Putting Bush onstage would make it virtually impossible for the audience to make an objective decision regarding conflicting arguments. This is, of course, why most of Brecht’s plays took place in distant lands and long ago.

I’m also reminded of an episode of SNL from the 90s, featuring Mark McKinney parodying Jim Carrey. It was bland and unfunny, because the punch of parody is the exaggeration, and exaggerating Jim Carrey is not an easy task. Likewise, any potential exaggeration of Donald Drumpf must necessarily be so deflated as to accomplish nothing. I still hear laughter, but it’s the laughter of recognition, the laughter of reaffirming our own biases. Those biases may be very accurate, but displaying them in a room of people who already hold them so we may all clap ourselves on the back strikes me as enormously masturbatory. I’m as big a fan of masturbation as the next person, but I don’t plan on spending hundreds or thousands of dollars on it, along with hours and hours of volunteer artists’ time (or underpaid artists’ time), all to solicit long-expected applause and plaudits of how clever I am: plaudits that were virtually guaranteed the instant the concept first emerged – “Let’s tell people how bad that guy we all hate is.”

AVOIDING THE APPEARANCE OF CONFLICT

On the social side of socio-politico, things seem a little more focused. Building someone up can accomplish a lot more than tearing someone down, especially if the idol in question is relatively unknown or uncelebrated (and I would definitely have put even Alexander Hamilton in that category), but when it comes to the promotion of disenfranchised groups, Chicago Theater’s goals seem both more immediate and more effective. This ultimately comes as little surprise, seeing as the monster we’re attacking in this realm is us.

Equal representation onstage and off. Making room for marginalized groups. Actively preventing sexual harassment. Impressive goals in the early 80s, but now just scrambling concessions that took an embarrassingly long time to effect. The worst offenders, not surprisingly, appear to be institutions that were large enough to exert power over the Chicago theater scene, but small enough to evade the notice of legal precedents and statutes that have been slowly transforming almost every other institution in the US for decades.

I recently worked with a fairly established theater company that wished to hold auditions in someone’s private home. They did not seem to see any problem with this. Even after explaining why new and vulnerable actors (which is exactly the demographic we were expecting to reach) might be made uncomfortable by this, there seemed to be little concern from the company involved beyond the frustration between refusing to please their unreasonably truculent director or spending $120 to secure a more neutral location (that, and a personal conflict with one of the managers of the location). This was a theater company that has recently been very vocal about actor agency and sexual harassment, and has historically shown dedication to inclusion long before its recent rise in popularity.

Although I am no stranger to harassment and disenfranchisement, in regards to more recent issues my role has primarily been one of listening. Even if theater companies are only pretending to take an interest in equity and actor agency, the results (such as they are) are real. I have certainly seen a sharp upswing in requests for actors and artists of color, and I likewise have enjoyed the self back-patting of shutting down semi-successful actors that whine about losing opportunities to these newly presented artists. Ultimately, I suppose insincere progress is certainly better than sincere regression. Some folks will no doubt find immediate parallels with our current election. So there’s some effective and poignant political theater there, even if it is a little too meta for my tastes.

WAGGING THE TWEET

So in my eyes (such as they are), the only real socio-political change happening in contemporary theater has been the relatively quick efforts to fix our own shatteringly enormous examples of racism, sexism, ablelism, really more -isms than I suspect I am aware of, and just good old fashioned oppression of the powerless by the powerful in all its forms. It’s nice, but finally kinda-sorta catching up with everyone else is not what I would call a political renaissance in the theater world. As for American theater’s effects on the rest of the world, they continue to manifest only in small human interest stories. Hillary Clinton quoting an enormously popular lyric months after-the-fact is a nice nod, I suppose, but not what I would call revolutionary.

What message does contemporary theater carry, that cannot be just as articulately communicated by someone’s five-paragraph blog, or even a well-written tweet? When it comes to provoking dialog, social media seems infinitely more effective. Of course, there are millions of arguments and polemics that preach to the choir and that reaffirm our own prejudices while accomplishing nothing more than making the writer feel smart, but there continues to be an infinitesimal number who are convinced to reevaluate themselves, or at least to see their political adversaries as people. Facebook is also perfectly capable of whipping up frenzied crowds of ill-informed pundits, who harass and belittle bloggers and celebrities until they flee from social media; but for good or bad, this medium seems far more effective than theater at accomplishing pretty much anything.

Mostly, what I see in “current events” theater is a marginally clever idea that is milked to exhaustion. I once saw a very ironic performance of Hamlet that turned out to be just two-and-a-half hours of “Remember Hamlet? Am I right?” I did not need to hear that joke, over and over again, for more than five minutes. Chris Jones fairly recently pointed out that parody leaves little room for complex evaluation. “Titus Andronicus meets Gordon Ramsay,” “Snow White meets Princess Zelda,” “Star Wars meets Game of Thrones meets anything.” It took me a while to come up with these examples, cause I had to try really hard not to think of something that I had already heard of or seen, lest I offend anyone. And of course there’s “Donald Drumpf meets whatever dictator hasn’t already been done fifty times, or sometimes that very dictator cause why not?” Then these poor artists, desperate not even for a career but just for something to do, have to invest months of their lives into a cute idea that stopped being funny months ago, exploiting and over-mining a concept what would have been better utilized as cosplay or fan art or even just a tweet, wasting time that would have been better spent even on something as artistically bankrupt as MacBeth on the Moon. Again.

MORE LIBERAL THAN THOU

A peacock’s tail serves no practical purpose. It is a costly encumbrance, and it exists only so its owner can show it off. “I am so well-adapted, I can afford to waste resources on this massive tail.” I like to use this analogy when describing pretense: pretending to be stronger than you really are, pretending to care about something you don’t, basically any use of resources committed solely in order to impress other people. In fact, this expression was part of one of my favorite monologues in A Thousand Times Goodnight, a play I wrote and will probably never stage again as the play and perhaps even the script itself is an excellent example of ignorant cultural appropriation, for which I luckily evaded widespread condemnation and was allowed to (eventually) wise up on my own time; such are the benefits of avoiding powerful institutions.

I imagine some people avoided my show because of its content, but by and large there were zero consequences for my actions. That might be a problem if I had gotten worse, but I think my behavior has improved since them (thanks to online communities, not theater). But for those who enjoy even a modicum of fame, or hope to achieve notoriety one day, there is no forgiveness or even tolerance. A significant part of the fanbase for the outstanding and remarkably inclusive cartoon Steven Universe subjected a fan-artist, part of their own in-group, to enormous levels of horrific online harassment due to some of her art’s regressive nature: this culminated in a suicide attempt. More recently, an actual employee of the show was subjected to similar harassment after being (perhaps understandably) accused of queer-baiting, but disappeared from social media before things became too harsh. Again, this is a significant part of the fandom itself, their own group, which is built around a show whose primary themes are love, forgiveness, and inclusion.

I mention this not as another screed about “liberalism going too far.” Such reactions may be justified; I don’t think they are, but I do not belong to the groups in question so my perspective is necessarily limited. I mention this because this potential for ostracism is one half of the in-group coin that defines contemporary art. Contemporary art, it has been decided, must carry a message, and that message must fall within certain parameters: inevitably, those parameters either make the target audience very comfortable, or discomfort them in safe, predictable ways. Ascribing to these prescriptions can win you praise (and funding) just as readily as straying might earn you death threats. So really, where’s the incentive to challenge anyone anyway? Is it any wonder that immersive theater is every bit as superficial and redundant as it was before Sleep No More came out? Is it any wonder that 1776 is popping up everywhere, with the casts mercifully more inclusive.

Recent experience continues to show me that the Chicago theater scene (and most every other theater scene, I suspect) has very little interest in effecting socio-political change in the community around them. As always, we are interested in what gives us more opportunities to produce, to make money off theater, and to market ourselves. When it comes to historically marginalized groups, it’s very difficult to begrudge anyone, seeing as their marginalization is exactly the issue, and championing inclusion onstage allows them to ameliorate that marginalization. As for evoking change outside the theater community, all I see is theater companies rushing to embrace whatever is popular. On Broadway, according to Hirsh, it’s fantasy and family pastiche. In Chicago, it’s endless parody and deflecting our own sins onto society as a whole. And whatever-is-popular is not an effective means of creating positive change for anyone other than yourself. The only positive change I see is theater slowly correcting its own backwardness, and this is the result of online (and in-person) activism, not the art itself.

That fact that even Hamilton does not seem to be creating any change outside of the theater community itself tells me that the advent of classic political theater is long-dead.