CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

The Tragic Inevitability of Wednesdays

*Plat*

Pratilda Shadow had been working in Chicago for about twenty years, and in all that time had effortlessly managed to evade pigeon droppings. It was such a sitcom cliche, in fact, that she had never given it any real thought. But now her black suit, which never seemed to fit right no matter how many times she had it adjusted (which was never because, after all, it never seemed to fit right no matter how many times she had it adjusted), had a geographically significant white mark running down the left breast, inching ever closer to the tiny, scythe-shaped pin that rested upon the lapel. Pratilda stood still in the middle of morning foot-traffic and stared down at the stain’s pilgrimage. Contrary to popular experience or supposition, the stain continued to run several seconds after impact. She waited. In time, the pigeon’s leavings made contact with the tiny scythe-shaped pin. Pratilda nodded in grim satisfaction, then made her way toward the office. Almost remarkably (though she largely felt that nothing necessarily bore remarking upon), not one person had bumped into her, shoved her over, or called her a bitch during the ten seconds that she stood in the middle of the sidewalk, immobile.

Though barely over five feet tall, Pratilda was not what one would call an insubstantial woman (a term she found endlessly, bitterly ironic). Squat and rotund, she become accustomed to eyes sliding over her, hesitating only to confirm that such a thing did indeed dare to occupy space before roving along to more conventionally compelling sights; of which Chicago offered many.

Finally, inevitably, someone bumped into her. A tall, athletic, square-jawed man in a blue button-down and gray pants walked by without comment, instantly blending into a sea of identical executives. Pratilda considered getting herself a second coffee before work. She pulled her cellphone from her slim black bag and checked the time.

7:26. She was going to be late. On top of that, a reminder appeared at the top-right of the screen: “Jonathan Moarney,” it read, “Lunch break – 10:17.” Pratilda’s eyes narrowed. She was not going to be able to change her jacket. She would just have to work without it, which would no doubt elicit commentary about the professionalism of her attire. She worked in a fairly relaxed office, and wore a black button-down blouse of an entirely conservative cut, but being a squat, rotund woman meant that her breasts inevitably drew more focus than the rest of her, so much so that passersby of all sexes seemed to feel that they existed quite deliberately and without permission, and that such existence required at least a judging glance, if not outright objection. Pratilda’s supervisors (plural) were by no means the most enthusiastic exercisers of this logic, but they were certainly adept students at the school of anatomical-commentary. Still, there was nothing to be done about it. Jonathan Moarney, 10:17, could not wait. Time and tide, as they say, waits for no man, and in Miss Shadow’s line of work the opposite was usually true as well. It should be noted, as she trudged onward toward her office, that Pratilda was decidedly not a tide.

Throwing caution to the proverbial, she crossed Jackson Street during a do-not-cross light, as so many people in Chicago’s Loop (the economic center of the city) so often did. There were essentially three types of pedestrians in the Loop: those who walked where they wanted when they wanted, those too timid to follow the example of the first, and those who required tacit permission from the first group before embracing their own capacity for solipsism. A small, bent man in his mid-fifties, evidently belonging to the third group, took a cue from Miss Shadow and slowly followed her across the largely inactive street. There was an audible thump, and Pratilda looked back, never breaking her stride, to see that the small man had been hit by a taxi not one yard from the curb. She continued on her way, indifferent, halfheartedly wondering who was going to take care of him.

Some clarification may be helpful at this point. “Take care of” should not suggest that Miss Shadow was wondering about ambulances or street sweepers. Pratilda had what many would call a hobby, which occupied the majority of her spare time, and which occupied the entire lives (such as they were) of many of her contemporaries. She herself would not call it a hobby, or a calling, or a passion, or any other equally patronizing term. It was a job. She did not receive compensation in any traditional sense for this job, but there were certainly benefits accrued, which was her sole motivation for continuing her (such as it was) employment.

Like many urbanites under the age of forty, Pratilda Shadow had two jobs. From 7:30 am to 5:00 pm, Monday through Friday, she was the office manager for Barvlok and Barvlok, a struggling accounting firm with (ironically) seriously mismanaged overhead. The rest of her waking life, and significant parts of the aforesaid hours as well when she could manage it, were dedicated to the commission, recording, and dispensation of death. She was, to put it in the broadest of terms, a grim reaper.

There were thousands, possibly millions, of such creatures in the world, floating about and reaping the souls of the recently deceased, ushering them on to their next mode of existence, and (at least in Pratilda’s case) filling out reams and reams of tedious paperwork afterward. Most of these grim reapers, possibly all others, were incorporeal in nature. It was an extremely convenient if somewhat boring style of manifestation, and if given the choice Pratilda would gratefully embrace incorporeality again. Sadly, no one had solicited her preference on the matter.

Miss Shadow had actually spent the majority of her existence as an Incorporeal. It was difficult to remember finer details, having not been constrained by time and, well, matter at that, well, time in her, well, life. As she recalled, she spent her time floating about mistily through streets and buildings and occasionally the Earth’s mantle, drawn toward the fatally condemned by instinct or something like it, siphoning up souls and dropping them off with blithe indifference, like an enormous and amorphous honeybee. The relevant information ascertained on this endless voyage was constantly transmitted to some unclear or unremembered entity via some no-longer-easily-understood connection she shared with it, and it with all her colleagues. Again, the honeybee metaphor applies.

Until one fateful day (though at the time she did not really understand what days were), her occupation drew her toward the parched wastelands of Las Vegas, Nevada, an area markedly bereft of Water. Being incorporeal and therefore brainless, she did not understand at the time that Water was the source not only of life, but also magic, fairies, mathematical truths, and generally all abstractions made constant. Excess of Water gave the Unreal life. It was often whispered that in the great expanses of the Pacific Ocean, massive quadratic equations could be seen breaking the waves like enormous Leviathan, consuming flying fish, small dragons, and the idea of Chivalry in their capacious jaws. It necessarily followed, then, that an absence of Water rendered a place exceptionally Real. Las Vegas was, in an example of infinite irony, one such abnormally Real place.

Pratilda was reasonably certain she had avoided Las Vegas for decades in her former existence, though at the time she did not understand what decades were. She often wondered how many other shades of death avoided the place as well, and what happened to all the neglected souls there. She never wondered very long, however: she was largely a pragmatic person.

However, for whatever terribly unfortunate reason, she had finally found herself drawn to Las Vegas some twenty-five years ago, where the excessive Reality had compressed Pratilda into her current, Corporeal nature. The sudden influx of gravity and hormones rendered her incommunicable for several weeks, after which time her employers (such as they were) insisted that enough was enough, and that her leave of absence would come to an end. They were unwilling to forego her services, despite the notable differently-abledness of being Real, and so a bureaucracy was erected to facilitate her continued work, in exchange for which she was allowed to stay alive despite the serious impediment of being several thousand years old. They issued her a black suit and identification (they chose the name “Pratilda,” but allowed her to pick her own last name; sadly, imagination was something that came with time), and redistributed her in Chicago, where they (and she) hoped the close proximity to Lake Michigan might one day restore her to Incorporeality. Pratilda suspected that such bureaucracy was proof that this sort of thing happened all the time, but was supremely uninterested in meeting other people like herself. She was bad enough company as it was. She also often wondered if a trip out into the middle of the Pacific might heal her of her newfound affliction, but thoughts of being digested by some bad poetry quashed her curiosity nicely.

She was sorely tempted, frequently, to offer a letter of resignation and let nature take its course. Sadly, Corporeality came with memory, and memory is a frustratingly unreliable means of accessing information. Miss Shadow could no longer remember what exactly happened to souls after death, nor whether death was an entirely pleasant experience. Regardless, her body came with all manner of anxieties and fears that prevented her from simply walking in front of a bus or starving herself. Despite her own best intentions, her body compelled her to continue existing. Although she had aged a little over the last quarter-century, she had every reason to believe this body was going to be the bane of her existence for several lifetimes to come.

At last, she had arrived at her office building. Barvlok and Barvlok was on the 63rd Floor, which was very expensive and just one example of the terrible decision-making process that dominated the firm. Pratilda had a number of ideas on how the accounting firm could save money, but the senior partners appeared to be supremely and paradoxically unconcerned about financial viability, and to be fair Pratilda was as well. She had been office manager there for over a decade, and people were starting to wonder how she stayed so (relatively) young-looking. It would be time to move on soon. Fortunately, Chicago was so populous, and the Loop so crowded, and city-dwellers so generally narcissistic and inattentive, it would likely be several centuries before she would have to leave the city entirely. Perhaps by then they would be building cities on the ocean, and she could risk poetic mastication in the hopes of returning to her former state.

Loop-dwellers, executives, wondered aloud quite frequently why cities like Chicago still existed. Why, after all, would anyone want to live and work in a city populated by trolls and fairy tale witches, where a poorly spoken insult just might pop into existence and exact revenge upon its speaker, where ancient gods would occasionally roll up in a party bus and drink an entire city block out of business? Why work in a city where an MDA (Master of the Dark Arts) could earn you an entry level position at Necromantic firms like Scoraxis and Smith (64th Floor, just above Pratilda)? Executives wondered these things in their offices. Hipsters wondered these things in their fair-trade hemp dispensaries. Part-time fast food workers wondered these things in their brokendown tenements. But they all knew the truth: cities like Chicago were the easiest places for an executive to get a retirement plan or a hipster to access creative outlets. As for the rest, they did not have the money or connections to leave. The fact that most successful cities were by large bodies of Water was an unfortunate reality inherited from the world before Reality decided to go into semi-retirement. The victims of this reversal of fortune, much like the cities themselves, were defined more by their inertia and habit than anything else.

Pratilda stared at her phone as the first elevator slowly climbed upward. Working on the 63rd Floor meant taking an elevator up to the 50th Floor, then switching over to a second elevator bank that would take her the rest of the way up. She was very much looking forward to leaving Barvlok and Barvlok. Sure, she had hoped to secure a pension before she left, allowing her to spend a little more time on her other job, but whatever let her spend less time in elevators would be nice too. More than once she had jolted awake at night, gasping and wild-eyed, haunted by visions of Godzilla (or a legally distinct yet similar beast) knocking over the building during a 9 am meeting. She was unsure how she felt about this potential eventuality.

Pratilda stared at her phone. A sloppily dressed, rail thin stork of a man was standing in the center-back of the elevator, and she could feel his red eyes boring into her. He was going to mention the pigeon-droppings, she could feel it. Yes, I am aware an abnormally large bird has taken an abnormally large shit on my abnormally large chest, thank you. At that moment, she would have given every dollar in her anemic bank account to prevent the inevitable commentary. Abnormally large bird. She wondered for a moment if it had been a pigeon after all. Maybe it was a giant bat or a gargoyle or Rodin (or a legally distinct yet similar beast). She was going to have to stop watching old Godzilla movies after 8 pm. She was going to have to stop eating sushi. She was going to have to start exercising more. She immediately shook off such ridiculous thoughts.

Pratilda stared at her phone. 7:36. The office should still be empty: no one would notice she was late, probably. It was pretty casual for an accounting firm. She would be fine.

Pratilda stared at her phone. “Jonathan Moarney” continued to glare back at her. She really, really did not want to take an early lunch that would not include any lunch. This sort of thing happened at least twice a week. Why was she so fat when she never got to eat? She was a grim reaper: shouldn’t she be as bony as the creepo staring over her shoulder at her chest? These were the sort of thoughts that ran through her head almost every time she rode the elevator. Better than claustrophobia, she decided.

“You got birdshit on your suit,” the creepo finally said. She ignored him. Before 9 am, Pratilda did not answer anyone unless they first said hello, good morning, pardon me, say, or offered some kind of similar preamble. She glanced down at her slim black bag and wondered idly where her taser was. She had not seen it in months.

They both got out on 50th Floor, Pratilda rapidly stalking over to the next elevator bank while the creepo said hello to a janitor. She continued to stare at her phone as she walked: she had no pressing emails or texts, it was just something to do. It was certainly better than interacting with people. Pratilda Shadow, despite having been an Incorporeal entity of perdition for thousands of years, was incredibly human.

The second elevator was halfway up to her office before Pratilda realized she was not alone. Using her peripheral vision, she discovered the lanky creepo had taken the same elevator. He was standing in the middle back wall, again. Pratilda was suddenly very preoccupied with her long-absent taser. Where was that thing? Under her bed, probably. She had never used it, anyway. She rarely went out at night, and was quite adept at sticking to crowded places during the day, despite her hatred of crowds. But no, it was the middle of the morning in the middle of the Loop. She was being paranoid.

Definitely.

The elevator opened on the 63rd Floor, and Pratilda impersonated a cannonball exploding outward as she propelled herself out the sliding doors. There, wedged next to a doorway leading to a few cramped offices, was the reception desk, where she would sit until the regular receptionist arrived at 9. To the right, a hallway led to the men’s room and a sea of gray, lifeless cubicles. Even now she could hear Gorplog, Carnifex, Tim, and the other nocturnal employees wrapping up their evenings and getting ready to head out. Miss Shadow marched with heretofore un-demonstrated alacrity to her seat. She turned and was about to sit when she caught sight of the tall, sloppy creepo standing there, staring at her.

She froze.

“Howdy,” the creepo offered. “I’m here to fix the lightning.”

“What?” she croaked. “They’re fine. You’re not Dave. What?”

The creepo’s red eyes widened in confusion. Pot-head, probably. “The uh, the lightning. For the computers. They’re run by lightning, right? I got a call late last night. I gotta fix the thunderclouds in the storm generator.”

Pratilda’s stare reached inconsiderate length. “Oh… Where’s Dave?”

“He’s out for the week.”

Pratilda glanced down. He was wearing a blue polo shirt. His black slacks looked like they had been crumpled up in the corner of a bathroom that morning. They were three inches too short. He had a name-tag on his shirt. It read “Jonathan.”

“Sorry,” she offered. “I’m Pratilda. Shadow.”

“Jonathan” he lit up, offering his hand. She did not take it.

“Jonathan… ?”

“Moarney.”

“Excellent! Yes! Welcome aboard! Yes! I’ll take you, I’ll get you, to the lightning, I mean. Yes!”

Jonathan Moarney retracted his hand and backed away. “Okay… cool…”

“Come on!” Pratilda was practically skipping down the hallway now. She might have time for a lunch after all.

In commemoration of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s shuffling off, Unrehearsed is joining Janus Theatre in Elgin, IL for a production of our short-cut of Comedy of Errors.

In commemoration of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s shuffling off, Unrehearsed is joining Janus Theatre in Elgin, IL for a production of our short-cut of Comedy of Errors. TO BE OR NOT TO BE?

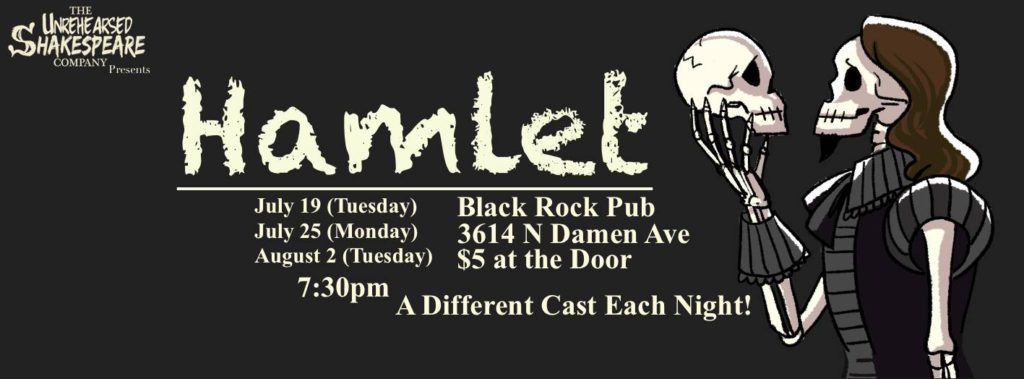

TO BE OR NOT TO BE?  CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1 After ten long years, my sci-fi one-act Butcher Boggle is finally being produced; as part of

After ten long years, my sci-fi one-act Butcher Boggle is finally being produced; as part of