The trouble with hills, generally, was that they inclined. Their inclines were not necessarily brutal; indeed they were often subtle and sometimes merely suggestive, and these latter descriptions aptly applied to the hill upon which Ursten and his erstwhile cohort were presently engaged. Still, just as comedy is often the alchemical progeny of tragedy and time, so the combination of time (the truest Philosopher’s stone most any alchemist was likely to come across) and a gentle hill would invariably produce fatigue. Fatigue and time then gendered irritation. Irritation, once incestuously coupled with his grand-parent, would birth that greatest of all bedevilments: second-guessing.

The trouble with hills, generally, was that they inclined. Their inclines were not necessarily brutal; indeed they were often subtle and sometimes merely suggestive, and these latter descriptions aptly applied to the hill upon which Ursten and his erstwhile cohort were presently engaged. Still, just as comedy is often the alchemical progeny of tragedy and time, so the combination of time (the truest Philosopher’s stone most any alchemist was likely to come across) and a gentle hill would invariably produce fatigue. Fatigue and time then gendered irritation. Irritation, once incestuously coupled with his grand-parent, would birth that greatest of all bedevilments: second-guessing.

Ursten was second-guessing himself. Could they pull it off? If they failed, would they die? If any should survive, would they happen to recall that they had embarked on this foolhardy adventure on Ursten’s own behest and perhaps, once the proverbial and subsequently literal dust of combat and subsequently funerals had settled, be inclined to point an accusatory finger at the young hero? And, once pointed, might that finger not then be followed by the throw of a fist, the swing of an ax, or the expectoration of a flintlock? These hypotheticals began to weigh heavily on Ursten’s collapsed shoulders as he trudged up the endless hillside, slowly gravitating toward the back of the mob by dint of both his weakening resolve and his weakening legs. Adding to the weight of these concerns and the responsibility of the lives of a few dozen people was the noticeable density of the burning torch in his right hand, which frustratingly seemed to grow heavier as he tired.

Perhaps it would be best, he thought, to allow his gait to taper further, and simply let his slapdash army pass him entirely. But of course, it was not his army any longer.

Once the citizens of Bucolivier had warmed to the idea of storming the tower, it was quickly decided that such a heroic endeavor could not be spearheaded by a short butcher’s son who was small in all the places a man aught not be small and large in all the places a man aught not be large. This decision was initially made by Hugo, the rock-muscled lumberjack, but it was quickly seconded and passed by the mob en masse. Seizing the knacking mallet straight out of the Ursten’s diminutive hands, Hugo hoisted the ersatz weapon on high and declared, “The monster dies tonight!” His rolling baritone, rippling out of a chest that would not have looked out of place on a statue of Jupiter, instantly ignited the villagers’ ire, which had to-date been brought only to a bare simmer by the enterprising Ursten. The Lothario-cum-Beowulf pivoted on the exclamation point and instantly marched out of town, not bothering to insure that his thoroughly riled entourage was well in step behind him. He knew. Such was the virtue of those blessed with square jaws and thick skulls.

Ursten did his utmost to keep pace with the longer legs, stouter muscles, and undeniably fiercer determination of the party’s new figurehead, but he was eventually pulled back by both the cruel caprices of nature and his own ebbing motivation. Only minutes ago, the thirst for vengeance had fired his demure lungs with divine fury, but the object of his passion had infuriatingly decided to erect her home two-and-a-half miles outside of Bucolivier proper. Once again, we see the perverse transformative powers of our old friend Time at work. For while a journey of less than three miles is nothing next to a loved one in danger or even the thrill of bloody revenge, it has quite a dampening power when that thrill is spread out amongst some thirty-or-more people. Particularly when some thews-bound nitwit is going to steal all the glory.

Perhaps if Hildi were still alive, Ursten might have been able to maintain some motivation.

There was no question that Hildi was dead. He had seen it happen, unfortunately. After spilling his heart to her, declaring a deep and abiding love that was born for the ages and that had existed ever since they had taken that bovine cross-breeding lesson via correspondence together, Hildi was tragically murdered by a donkey’s kick to the head. True, Hildi had backed into Dowsabel’s stall, which should not have been left open. True, Hildi’s eyes were wide and glazed, and a rictus smile was painted on her face as she backed away from Ursten’s sincere epistles. True, Ursten may have slightly raised his voice when his declaration was not immediately met with enthusiasm. And yes, true, Dowsabel’s braying and kicking did appear, to the unpracticed observer, to be immediately precipitated by Ursten’s shouting. Fortunately, there were no other observers, practiced or otherwise, save the gratifyingly laconic donkey. So Ursten was free to carry Hildi’s lifeless body out of the stall, bespattered with entirely genuine tears, until his arms gave out and he deposited her upon the ground with a wail that would have compelled Lear himself to ask if he might tone it down just a bit, not twenty meters from the barn. There, the butcher’s son waited patiently for a sufficiently sized crowd of mourners to gather before revealing the tragic details of Hildi’s decidedly prosaic end.

Alas, before a good dozen people could emerge from their homes, an enormous metal giant appeared and stole the body.

The Golem, as it was known in the village, unquestionably had come from the tower. Many a villager had claimed to have seen it late at night, stalking about the perimeter of that shunned place: standing guard against the ghouls and goblins that were surely drawn to such a nest of evil, hunting down and slaughtering the wolves and black cats that could smell the devil emanating from within, and (according to some) tending the turnip garden round the back. Tending a turnip garden at midnight was, according to many villagers, the greatest accusation of evil thrown at the monster’s feet. The question of what exactly these villagers were doing near the tower, two-and-a-half miles out of town, around midnight on what was invariably a work-night, was rarely broached. On those rare occasions, the accuser would rapidly develop an intense interest in their beer, a chemical which was always to hand when such stories were told.

Twice as tall as a man and thrice as broad, built from Hell-fired steel, yellow-bright coals burning where its eyes aught to be, the Golem had always been left to its own devices. There were two such motivations for this remarkably laissez-faire attitude: one, the beast always kept to itself and never traveled more than a hundred meters from the tower; and two, the beast looked quite capable of crushing a human head with one hand. Only now with a mob of about twenty-five concerned citizens, galvanized by its unprecedented invasion into the village proper, did they dare march upon the creature’s home.

Was that number accurate? Ursten felt quite confident that there had been almost three dozen of their task force when they had first set out. Had the master of the tower sent out other, subtler servants to trim their numbers? Or, more likely, had they simply succumbed to the same dark magic that was now threatening to overpower Ursten himself: doubt. Through the crowd, he could still see Hugo’s prodigious arms pumping up and down in time to some Saint-Georgian march that rang only in his head. The butcher’s son took a deep, burning breath and doubled his efforts. He was the hero here. He was going to show that corpse-snatching demon-spawn that its actions had consequences. He was going to show Hugo, Hildi’s parents, and the town as a whole that he was worthy of their (and, were she capable of it, Hildi’s) admiration. And most importantly, he was going to show everyone that this beast was unquestionably the villain here, and no one else.

If only the damn hill would peter out at some point.

Ursten had not even made it halfway to the front of the crowd when everyone stopped, jostling into one another as inertia reassembled the group. The tower stood before them. A patchwork of stone and lime, metal and bolts, wood and nails, and some strange unholy materials that no one recognized, the tower was the epitome of “that which should not be.” The fact that a giant made out of blackened steel lived inside, along with whatever other foul creations, was almost redundant. The tower leaned, and in more than one direction. Narrow, at least ten stories high, and no doubt filled with obnoxiously spiraling stairs, it would be easy and necessary to tear it down. Ursten briefly reflected on how often the easy and the necessary seemed to coincide in Bucolivier. Everyone else, however, reflected only on Hugo’s booming declaration.

“Come out, Witch!” he roared for the second or third time; Ursten had not really been listening. “Foul grave robber!” he bellowed further. “Despicable corpse snatcher!” An awkward pause followed. “Evil…” he added, “… woman…” Desultory applause flittered from the mob, trying to encourage their de facto spokesperson. The profile of his jaw, beautifully silhouetted against a particularly light patch of tower by the setting sun, nodded brusquely. “Come out, Witch!” he demanded again, having evidently exhausted his material and deciding to revisit the standbys with which he had become comfortable.

The mob began to chant, “Come out, Witch!” with rapidly rising intensity. Ursten sympathized with them, but the concept of chanting at a witch seemed somehow counter-intuitive, perhaps even hypocritical, so he kept his own council. It was perhaps unavoidable, then, that the chanting indeed worked.

An enormous boom erupted from the tower’s door, silencing the crowd. Hulking black iron with a dragon’s head embossed upon its front, the door looked as though even Hugo would be unable to move it upon its hinges. Nevertheless, it slowly groaned open. A few of the villagers gripped their pitchforks more steadily. Fewer others held their torches resolutely in front of their own bodies. Fewer still held up knives or axes. The rest suddenly and embarrassingly realized that they had come unarmed to wage war against a witch and her army of monsters, and collectively leaned back on their heels.

A figure emerged from the dark doorway.

Although still terrified, the villagers breathed a collective sigh of relief to find that an enormous metal warrior with titanic arms and a demonstrable lack of concern for social norms was not exploding out of the tower with a draconic roar, ready to tear each of their limbs off and subsequently mix them in a jumble before translating them into modern art. Instead, a tall and narrow but nevertheless un-intimidating shadow appeared, soon to be illuminated by a torch held aloft by Ursten, who had finally forced his way back to the front of the crowd.

There stood a woman in her thirties, a bit worn by time but clearly still vital. Her skin and hair were both darker than was the norm in Bucolivier, but the Bucoliviens considered themselves nothing if not cosmopolitan in their attitudes toward strangers. Of course, they also considered themselves educated and forward-thinking, so their perspectives might be discarded with confidence. The Witch, as she was so called, had large and opalescent eyes that seemed entirely too eager to reflect the hungry flames of the nearby torches. Her decidedly masculine outfit, which appeared to be various shades of blue and gray in the dim light, was of a decidedly western and decidedly dandy-ish cut. She looked almost like a pirate, which would have been cause for suspicion even if Bucolivier were not over five-hundred miles from any significant body of water. But then, the Bucoliviens considered themselves nothing if not accepting of alternative lifestyles in their little village. Of course, they also considered themselves forbearing and democratic in their approach to criminal justice, so again we see how isolation can give a community a false impression of its own progressiveness. Still, it must be admitted that even if the people of Bucolivier were as willing to embrace people fractionally different from themselves as they thought, this woman still had some serious explaining to do. She had, after all, stolen a dead body from the middle of town in fairly broad daylight. Or rather, a gigantic metal man believed to be under her employ had done so. Indeed, now that everyone considered it, the gigantic metal man alone was something for which they felt they were owed an accounting.

Instead, silence followed. The torches guttered in the very gentle breeze. Ursten, being slightly more reflective than his fellow townsfolk, took the time to consider that this seemed like a metaphor for his entire life up to that point.

Long after the silence had stretched past impolitic and just became uncomfortably forced, Hugo cleared his throat and considered his options. “Listen here, Witch.”

“My name,” she countered in a well-supported contralto, “is Doctor Luciana de la Luna. Sir.” The ‘Sir’ was heavily marinated in overtly-insincere polity.

Ursten was close enough to see one of Hugo’s well-defined eyebrows climb daringly up his brow. “Doctor, madam?”

“Correct.” There was, again, silence. A thrum filtered through the crowd, and steadily everyone began to get the impression that they were somehow not as overwhelming a force as their paragon had led them to believe.

Hugo, however, was not one to allow doubt to penetrate his heroically broad skull. “Madam-”

“Doctor,” the Witch reasserted.

Hugo muttered something in response, which a very charitable listener might have discerned as “Doctor.” the Witch gracefully accepted this as sufficient to her needs.

“Yes? How may I help you?”

The Salvation of Bucolivier drew himself up to his full and impressive height and orated, “You have nabbed one of our citizens. We demand you return her to us, so we may lay her in proper Christian burial!”

“Yeah!” said someone in the crowd. Whoever it was, evidently embarrassed by the lack of assistance, added nothing more.

Doctor Witch shifted her weight. “And what good do you hope to effect with this Christian Burial of yours?”

“We mean to save her soul from the Devil, woman; a state of grace I do not expect you to understand!”

Someone in the crowd seemed about to shout something, but quickly stopped themselves short.

“Her soul?” she repeated, dripping with put-upon skepticism. “I should think her life were a rather more substantial concern. Not to mention a more easily substantiated one, but that is purely academic.”

Had Ursten turned around at that time, he would have seen a sea of blank faces, their eyes rapidly running across the words they had just heard and attempting to decipher their meaning. Sadly, Ursten was too busy doing just that himself and consequently saw nothing.

Hugo, ever the proactive sort, picked a word he recognized and pressed on. “Her life is gone, Witch! She has been murdered by your demon Golem… thing!”

“That’s right!” shouted another voice in the crowd. There was a small murmur of agreement, but no one seemed able to revive the furor that had first propelled them up this accursed hill.

“Did he? That was not my impression at all. He assured me that the girl was already unconscious when he, as you say, nabbed her. That boy there was wailing in front of her like some tenor who had failed to properly warm up. At least, according to my, as you say, demon Golem thing.”

Hugo was not known for his subtlety, even by himself, but he had a keen ear for when he was being mocked. Essentially, any time he did not fully understand the purport of someone’s sentence, he assumed a slight was being offered. He responded habitually with physical threat, which up until this very evening had always had predictable and desirable results for him. Sadly, this night was going to have the same perversely transformative effect on his luck that Time seemed to be having on everything else.

“Listen here, Witch,” he bellowed, showing a complete disregard for both manners and social improvisation, “You will return Velma’s dead body to us–”

“Hildi,” Ursten whispered.

“You will return Heddy’s dead body to us, ” he sneered, “or we shall slay your evil giant, tear down your God- and carpenter-forsaken tower, and rescue her ourselves. And I,” he continued, a malicious glint in his eye, “shall use this mallet to properly arrange your foreign, female brain into something more God- and man-fearing.”

There was a collective intake of breath. Evidently Hugo was unaware of just how cosmopolitan and tolerant Bucolivier considered itself to be. At the moment, however, they were far more concerned with how a sorceress with airs of medical pretension would respond to the addition of insult to hypothetical injury.

So intent was everyone on the exchange, that they had failed to notice the cyclopian brute now standing directly behind the Witch herself. Without averting her gaze, she reached up and rapped her knuckles against the giant’s metal hide. “That’s an impressive list of threats,” she proffered. “I believe the first box you need to check off is the slaying of my evil giant, is that correct? I leave you to it.” As she circumnavigated the horrendously humongous humanoid, she continued, “when I hear your conspicuously absent sledgehammers and pickaxes tearing at my tower, I shall return. Or perhaps sooner, depending on how bored I become.” By then, she had vanished into the darkness, well obscured by the long remarked-upon but not-at-all-anticipated monster.

Again, Hugo cleared his throat. He felt it made him seem intelligent, and if he only knew what was to occur over the next ninety seconds, he might have done it a few more times, in order to leave a greater impression of himself. “Stand aside, beast,” he commanded, “or I shall slay thee.

Ursten took a pointed step to the side.

The beast said nothing. Its eyes glowed like molten gold.

Hugo attempted to step around the beast. It intercepted him. He tried again. He failed again.

To his credit, Hugo took a moment to turn and look at the crowd behind him. Perhaps if he had been alone, he might have made a different decision. But then, if he had been alone, he never would have come in the first place. He looked the giant square in its sternum, stuck out his jaw, and reared back the knacking mallet.

The Golem’s claws were clamped on his wrist before he could even swing. It lifted Hugo bodily into the air, easily two meters off the ground, swung him around like the proverbial dead cat, and flung him down the hill. Ursten tried to watch his mallet as it flew off in another direction entirely, but it was too dark, and the relic of a now bygone era was quickly swallowed by the night. Hugo’s scream soon followed.

Ursten turned back to see that he himself had drawn the eye of the Golem. He gulped, very audibly. He could feel everyone’s eyes on his back. He could also very easily feel them all remembering just whose idea it had been in the first place to traipse all the way up here, ruining a pleasant evening of darts or drinking or fasting and repentance, to join this amateur witch-hunt which was evidently a doctor-hunt and now had become some sort of amateur discus competition.

Ursten gulped again, though this was more to stall for time. He took a single step forward. The Golem did not move. He reared back his torch, having no other armaments, and prayed his countrymen could not hear the whimper that escaped his throat.

Then he suddenly realized: he had not whimpered. That sound had come from behind the giant beast. Eyes wide in horrified anticipation, Ursten craned his head all the way up to peer into the Golem’s utterly impassive eyes. The creature was perfectly still. He lowered his torch very slowly, very deliberately, and very carefully, back to shoulder height. In an inauspicious echo of the erstwhile Hero of Bucolivier, Ursten cleared his throat. Then he asked, “Did she say… ‘unconscious’?”

A slim form slunk from behind the Golem. She was wearing a country dress, still stained with cud and other less pleasant things one might find in a barn. Her gilded ringlets were largely obscured by heavy white bandages that were wrapped around her head, but her large and accusing blue eyes were still very visible.

Ursten gawped openly, the monster all but forgotten. “Hildi…” he whispered. “You’re… alive?”

Hildi was still rubbing the back of her head, but she had sense enough to roll her eyes at him. “Obviously, no thanks to you… wait…” He free hand rose slowly and damningly into the air, and it was soon pointing the long-feared accusatory finger at the poor butcher’s son. “You killed me.”

“But,” Ursten sputtered, “I mean… I didn’t…”

“You did!” She shouted.

A voice in the crowd gasped, then exhaled, “No!”

“Yes!” Hildi insisted, “he most certainly did.”

Silence fell like a redwood. Unwillingly but inescapably, Ursten turned to face the crowd. There he saw what was definitely twenty-four pairs of eyes glaring at him. The God-fearing fury, the blood-rising march, the irritation of time, and the frustration of defeat was now transformed, transmuted as though by the scholars of old, into unmitigated hate, and it was all pointed directly at Ursten.

The people of Bucolivier had upset their entire evenings with the intent of performing righteous murder, and now the most convenient of targets had presented itself to them.

Ursten gulped, again. Perhaps, if he had been a little more realistic about this future, he might have vocalized something more dignified.

Meanwhile, up in the highest room of the damned tower of the Witch of Bucolivier, Doctor de la Luna had just changed into her nightgown and was settling into her remarkably comfortable bed. A strange glass globe was emitting powerful rays of light beside her bed, which allowed her to read a book whilst propping her head up upon a pile of pillows. She narrowed her eyes at the pages while enduring the pounding of heavy feet upon a spiral staircase. Eventually, an enormous figure entered her bedroom.

“Every time I read this book,” she said aloud, “I forget the street Harry lives on. No idea why. How far did you throw him, by the way?”

Some gears seemed to be grinding together in rhythm within the giant’s head.

“Two-hundred meters? A man that size? That is impressive.”

The gears juddered.

“Well we can only see so many people buried alive before we do something. I am entirely sympathetic to your actions, David. Entirely. We’ll wait a week for things to die down, and you can go back into town and steal the horseshoes when it’s well after dark.”

The gears continued to grind. The monster approached the bed and laid a small envelope upon the covers. Doctor de la Luna set down her book, using her index finger to mark her place, and examined the delivery with her free hand. “A letter?”

The beast ground some more as it returned to the staircase.

“The postman came to a mob riot? How very derelict of him. And he was carrying this letter? At night? Why is he only delivering it now?”

The monster’s head was just visible, peaking above the lip of the descent.

“Of course,” she nodded, “why would anyone have bothered to learn my name before tonight? Typical.”

The Golem grinded a bit more, with some decidedly upturned inflection.

“Oh? And what could such a small and unimposing young man have done to elicit such brutality?”

The thing called David gave a rather long answer.

“And for that they tore him apart?” She tutted, setting the book aside unmarked. She considered as she opened the letter, then said “I suppose we might as well see just how far my medical studies have deteriorated. Bring him in and stow him in the basement. I’ll deal with him tomorrow. Bloody Frankenstein, I’m turning into…” she trailed off.

The fearsome Golem of Bucolivier disappeared down the stairwell, clumping all the way.

Doctor de la Luna, the Witch of Bucolivier, narrowed her eyes as she read. “Who the hell is King LeMer?” she asked no one.

An unnecessary distraction, answered no one.

“My thoughts precisely.” She tossed the letter into the middle of the floor and clapped her hands twice. The light went out, swathing the tower in shadow. “Damned letters,” she muttered whilst turning over in bed. “Damned peasants… damned time machines…”

Damned everything, offered no one.

“Quite so,” she agreed with no one. “Quite so.”

In less than a minute, she was asleep.

The funny thing about tinker-trogs (or troglodytus mechanicus, as suggested by an overeager taxonomist who would later prove, in the eyes of his employers at least, to be as redundant as the above suggestion), is that they are deliberately built incomplete. Perhaps “funny” isn’t the best term, but then there is a reason that the Theatre is represented by two divergent masks in close proximity.

The funny thing about tinker-trogs (or troglodytus mechanicus, as suggested by an overeager taxonomist who would later prove, in the eyes of his employers at least, to be as redundant as the above suggestion), is that they are deliberately built incomplete. Perhaps “funny” isn’t the best term, but then there is a reason that the Theatre is represented by two divergent masks in close proximity.

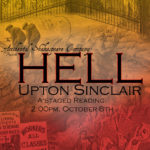

PROLOG

PROLOG October: The

October: The